Just over a fortnight ago, the federal government handed down the 2020 budget and the main theme as expected was the massive debt the COVID-19 pandemic has plunged the Australian economy into.

Included in the numbers handed down on the night was a forecast that the country’s net debt will peak in 2024 at $944 billion, which is the equivalent of a whopping 44 per cent of gross domestic product.

It’s small wonder that just about all of the measures handed down were focused on repairing the economy as quickly as possible. As such, superannuation, and especially the SMSF sector, was largely left alone.

There were only two superannuation measures, the first being that from 1 July 2021 an employee’s nominated super fund will be effectively ‘stapled’ to them for the duration of their working life, meaning all compulsory employer contributions will directed to it.

The second was to introduce annual performance testing of MySuper products, also from 1 July 2021.

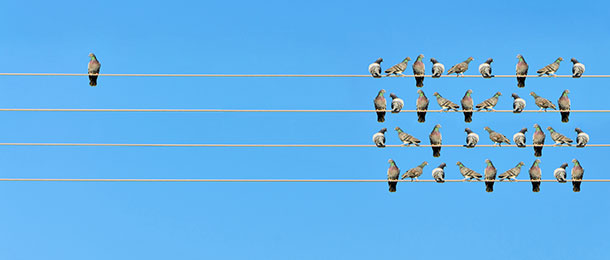

I think we can agree this constitutes minimalist change to the retirement savings system, especially when you compare it to some of the budgets past.

While neither announcement is SMSF-specific, it doesn’t mean there aren’t implications for the sector.

Some commentators have predicted the appeal of SMSFs could now increase under the new stapling rules, particularly given the increase in maximum membership from four to six individuals, as larger family units will now be able to establish their own fund that will allow their children to consolidate their employer super contributions from the time they enter the workforce.

There has also been an argument that the benchmarking of MySuper products, and the consequences for underperforming funds, could boost SMSF establishment numbers for individuals not necessarily wanting to have downside performance constraints placed upon them when looking to maximise their returns.

But there has also been speculation the benchmarking measure could eventually be extended to include SMSFs, although no one is quite sure what that would look like or the effect it would have on trustees if a fund was found to be underperforming.

On a positive note, the current performance comparison measure could already be of benefit as a benchmarking tool for SMSF trustees.

So we should all be grateful the super system has been given some respite from government tinkering for at least 18 months, but perhaps we shouldn’t get too comfortable with this notion.

I started this editorial noting the net debt for the economy has been forecast to peak at $944 million in 2024. If we look at the history of governmental fiscal policy in recent times, there is one lever it has been only too willing to pull in the name of economic repair and that is superannuation.

Some recent examples you might remember are the introduction of the $1.6 million transfer balance cap and the failed proposal from the Labor Party to scrap the refund of excess franking credits, sometimes referred to as the SMSF tax.

It means we can probably expect more taxation pain for SMSFs in the short term. What it will look like no one knows, but it has been discussed among sector stakeholders it could begin with a tax on pension drawdowns.

For now though let’s be thankful for small mercies that, for a short period of time at least, trustees will not have to deal with any legislative risk – even if it did take the catastrophic economic effects of a pandemic to facilitate the result.